Plastic Forming Technologies: Choosing the Right Process for the Right Part

Thermoforming is a go-to method for making all kinds of plastic parts, from simple packaging to complex machine covers. But here’s a little secret: many engineers and product developers mostly know about the common thin gauge thermoforming process—basically the vacuum forming stuff used in packaging—and often don’t realize there are other thermoforming techniques that might actually be a better fit for certain parts.

As a customer or product stakeholder, it’s not always the case that the final manufacturing process is chosen by you. However, having a solid understanding of what’s possible—and what’s actually being done—can make a huge difference. It helps guide product design decisions, avoid costly mistakes, and ultimately get a better final part that fits both function and budget.

This article breaks down the main types of thermoforming—including vacuum forming, pressure forming, drape forming, cavity forming, and twin sheet thermoforming—and when each one actually makes sense to use.

What Is Thermoforming?

At its core, thermoforming is just heating up a plastic sheet until it’s soft enough to mold over a shape, then letting it cool so it keeps that shape. Think of it like warming a piece of candy until it’s bendy, then molding it over something until it hardens again.

There are two key ways to think about thermoforming: by how thick the plastic is, and by how it’s shaped.

Thin gauge thermoforming uses very thin plastic sheets—like those flimsy trays that hold your strawberries or the clear plastic blister packs that hold gadgets. It’s perfect when tons of parts need to be made quickly and cheaply.

Heavy gauge thermoforming is more like thick plastic panels or lids on outdoor equipment—stuff that needs to be tough and last a while. This thicker plastic means the process usually takes a bit more time and care but gives a stronger final product.

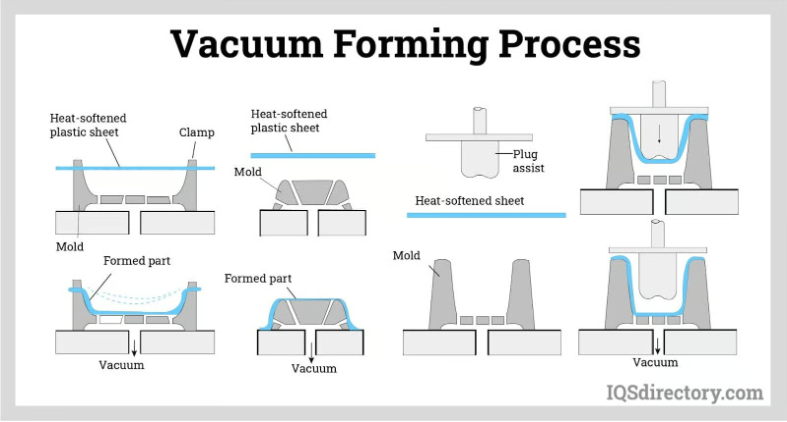

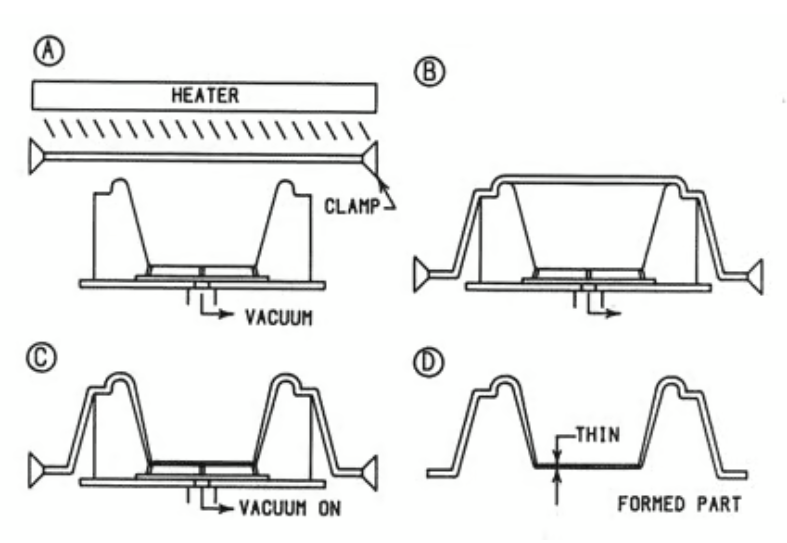

Vacuum Forming

Vacuum forming is the “classic” thermoforming process. Imagine heating a plastic sheet until it’s soft, then sucking the air out from underneath so the sheet gets pulled tight over a mold—kind of like when a vacuum-sealed bag clings to your leftovers.

It’s quick, cheap, and great for simple shapes—think plastic clamshells holding a toy or trays for cookie dough. But because it only pulls with the power of normal air pressure (one atmosphere), it can’t force the plastic into every little nook and cranny. So edges end up a bit rounded, and tiny details get lost.

Also, vacuum forming generally prefers thinner plastics. Try to force a thick sheet with just vacuum pressure, and it won’t stretch nicely. That’s why it’s perfect for those lightweight, disposable packaging parts but not great if strength or fine detail is needed.

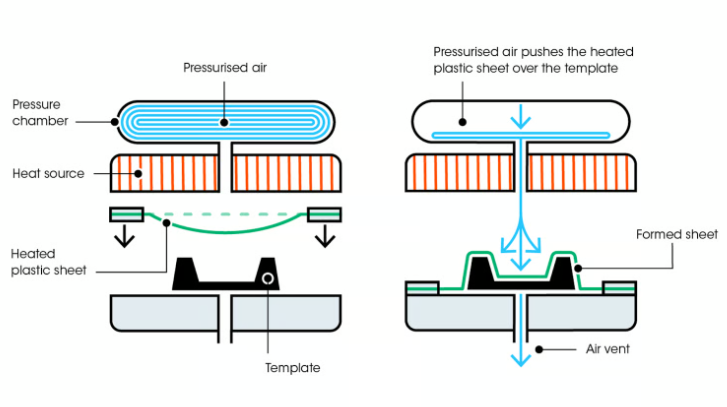

Pressure Forming

Pressure forming takes vacuum forming and kicks it up a notch. Instead of just sucking air out from under the plastic, it pushes air down on top as well—think of it as giving the plastic an extra firm hug. This added pressure can be up to 60 PSI, way stronger than just a vacuum.

What does this mean in real terms? It means parts come out sharper, with crisp edges and much more surface detail—almost like injection molding, but without the huge upfront tooling costs.

This is the go-to if making something like a sleek medical device cover, a detailed dashboard panel, or a fancy branded casing where looks and tight tolerances matter.

Pressure forming can also handle thicker plastics better than vacuum forming, so parts come out sturdier. The trade-off? It costs more and takes longer to set up than vacuum forming, but if the job demands quality, it’s worth it.

Drape Forming

Drape forming is the chill method of thermoforming. Heat up a plastic sheet and just drape it over a mold—gravity does most of the work, with maybe a little push to help along. Think of it like throwing a soft blanket over a box and letting it settle into place.

This method is great for making simple curved shapes, like skylights, signs, or decorative panels where smooth, flowing shapes matter more than sharp details or complex features.

However, because it’s mostly gravity doing the work, drape forming isn’t great for detailed or intricate parts, and it needs thinner, more flexible plastics so the sheet doesn’t crack or get too thin.

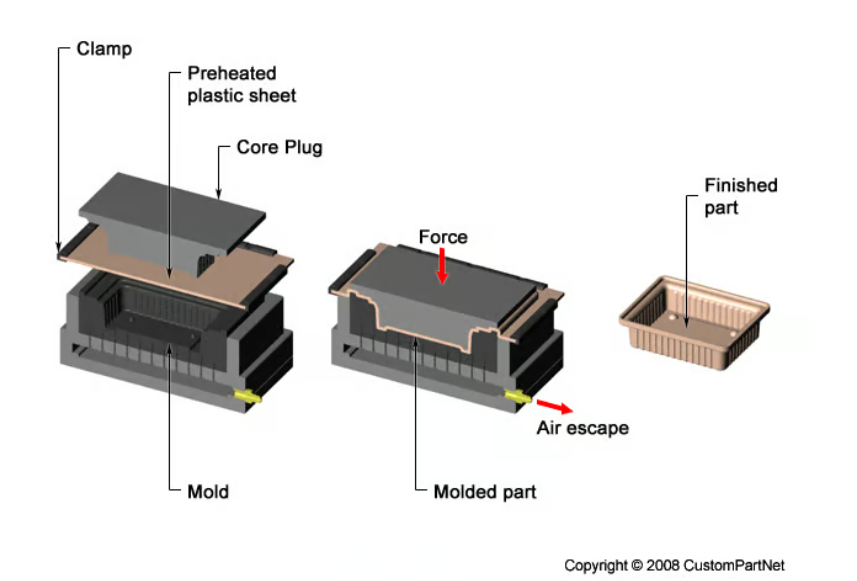

Cavity Forming

Cavity forming is like vacuum or pressure forming but focused on pulling the plastic into a hollow mold, creating a part with an internal shape. Imagine pressing a soft sheet of plastic into a bowl to make a container—that’s cavity forming.

It’s perfect for packaging like clamshell boxes or product housings with detailed insides. But it requires careful mold design—vents to let air escape, and thoughtful shaping to avoid the plastic getting too thin or wrinkling.

Cavity forming works best with medium-thickness sheets, balancing flexibility and strength. Push it too far with deep cavities, and parts might need trimming or other fixes after forming.

Twin Sheet Thermoforming

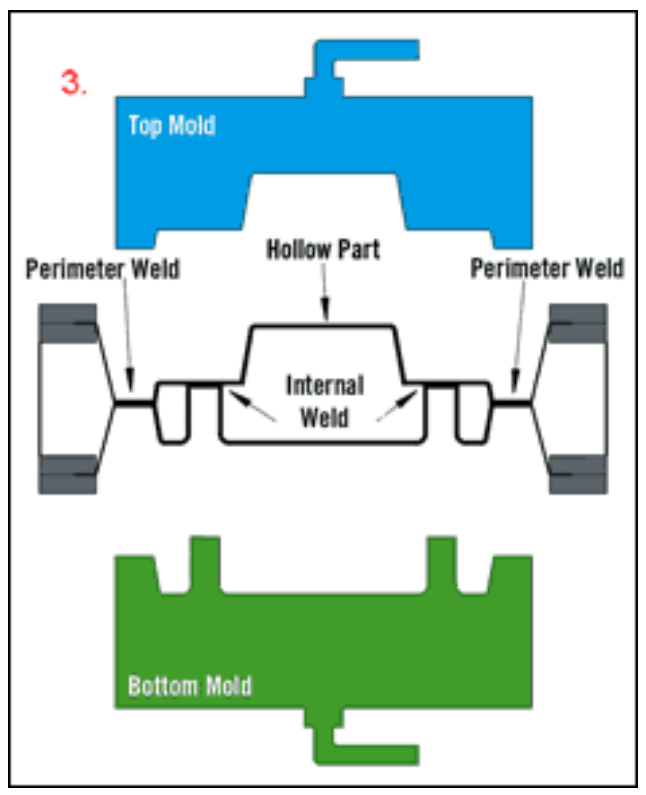

Twin sheet thermoforming is the heavyweight champ when it comes to complexity. Two sheets of heated plastic are formed separately and then pressed together to fuse into one part. This lets manufacturers make hollow, multi-layered pieces that are strong and lightweight.

Think of things like coolers, pallets, or ductwork where a hollow but sturdy shape is needed. It’s a neat trick that can replace more expensive methods like blow molding in some cases.

The catch? Twin sheet needs fancy tooling and precise timing. It’s more costly and complex, but the results are parts that are hard to beat for durability and function.

Conclusion

Thermoforming is a powerful toolbox of techniques, each with its own sweet spot. It shines when lower upfront costs, fast turnaround, and design flexibility are needed—especially for parts too big or costly to make with injection molding.

For fast, cheap, and simple parts, vacuum forming is often the answer.

When fine detail and sturdiness matter, pressure forming steps in.

For smooth curves and simple shapes, drape forming does the trick.

Need hollow parts or containers? Cavity forming handles that.

Looking for hollow, multi-layered parts? Twin sheet thermoforming is the way to go.

However, it’s easy to fall into common traps—like assuming all thermoforming is the same, ignoring material thickness limits, or designing without manufacturing constraints in mind. Being aware of these pitfalls and understanding the differences between processes helps guide smarter decisions, avoids costly rework, and ultimately results in better parts delivered on time and on budget.

Knowing the differences among thermoforming methods empowers better collaboration between designers, engineers, and manufacturers—leading to products that look great and perform even better.

Make sure to follow the link to keep up with us! You can get a heads up with events we’ll be at, content we have coming up, and much more!

https://lnkd.in/git9pHFq