Designing for Circularity: A Research Perspective on Material Choices in Plastic-Based Product Engineering

Introduction

As environmental regulations tighten and consumer awareness grows, product engineers are being called upon to design with sustainability in mind—not only in use but across the product's entire lifecycle. Nowhere is this more evident than in the selection and use of plastics, which, while highly versatile and economical, present formidable challenges for recycling.

Despite advancements in polymer science, only about 9% of plastic waste is recycled globally. This disparity stems not from technological limitations alone but also from upstream design decisions that impede recyclability. In many cases, the choice of mixed resins, additives, or incompatible components makes post-consumer recycling technically or economically unfeasible. Thus, engineers occupy a critical position in reversing this trend by designing for recyclability from the outset.

1. Understand Resin Behavior, Recycling Pathways, and Sorting Complexity

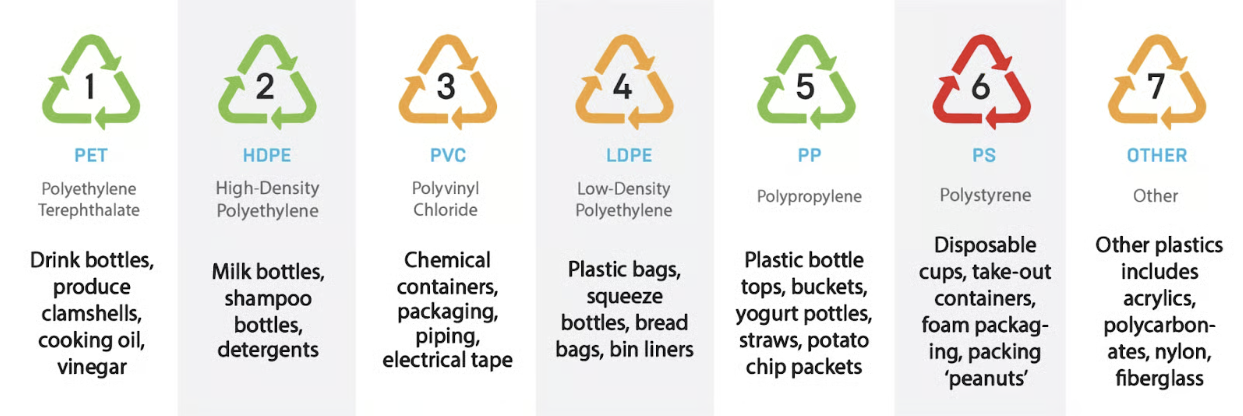

Plastics are widely used for their versatility, but they come with a complex range of chemical properties and behaviors that impact recyclability. At the heart of this challenge is the resin identification system—numbered #1 through #7—each corresponding to a different polymer type (e.g., PET, HDPE, PVC). These materials vary in their melting points, mechanical performance, and interaction with other substances, which directly affects how they can be recycled and reused.

From an engineering standpoint, it’s not enough to select a plastic solely based on strength, formability, or cost. Engineers must also factor in how the material will behave at its end-of-life stage—particularly whether it can be effectively sorted and recycled in real-world systems. This is where the compatibility of the resin with existing recycling infrastructure becomes critical.

Importantly, the processes used to recycle and sort plastics vary significantly depending on the facility, technology, and regional regulations. This variation can introduce unnecessary complexity into product design and production, especially if the product is distributed across different markets with inconsistent recycling capabilities. However, understanding these systems allows engineers to calibrate their design ambitions, striking a realistic balance between technical performance and environmental responsibility.

Key Sorting and Recycling Technologies

Recycling begins with sorting, and the efficiency of this step is what often determines whether a material is actually recycled or sent to landfill. Engineers should be aware of the following commonly used technologies:

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

This optical sorting method is widely used to identify plastics based on their unique infrared reflectance signatures. However, it has limitations—dark or carbon-black-colored plastics, for instance, are often invisible to NIR scanners. Engineers can address this by specifying NIR-detectable pigments or designing with transparent or light-colored plastics when possible.Density Separation (Float-Sink Tanks)

Different plastics have unique densities. For instance, HDPE floats while PET sinks, allowing for physical separation in water tanks. Choosing plastics with distinct density profiles—or avoiding combinations that interfere with float-sink processes—can improve downstream recyclability.Manual and Robotic Sorting

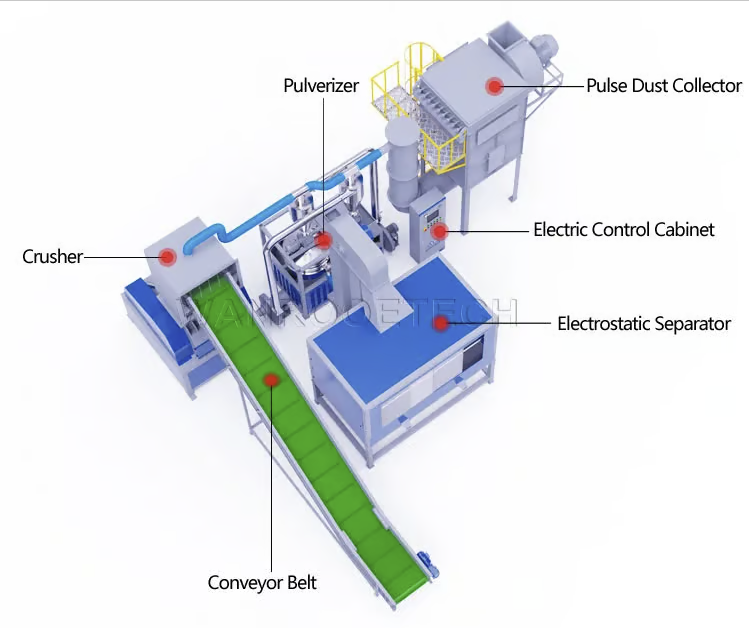

Some facilities still rely on manual labor or now increasingly use AI-guided robotic arms that identify and sort materials by shape, color, or texture. Designs that include mixed materials or obscure labeling can confuse both human and machine sorters, reducing recovery rates.Electrostatic and Triboelectric Separation

These are specialized methods used to sort finely shredded plastics based on their electrical properties. They’re useful for processing mixed plastic waste streams, though not widely available in all facilities.

Types of Recycling and Implications for Design

The next step—recycling itself—can be approached through several pathways, each with its own design implications:

Mechanical Recycling

The most common method, this involves melting and reprocessing plastic into pellets for reuse. It works best with clean, monomaterial waste streams. To support this method, engineers should minimize the use of multi-layer films, bonded materials, or incompatible additives that degrade during reprocessing.Chemical Recycling

Involving processes like pyrolysis or depolymerization, this method breaks down plastics into their molecular components for reuse as feedstock. It offers potential for hard-to-recycle plastics, but is still limited by energy costs, infrastructure, and scalability. While promising, engineers should not rely on chemical recycling to justify using poor design practices like multilayer laminates or mixed resins.Energy Recovery

Though sometimes included in waste management systems, this approach (incineration with energy capture) is the least desirable from a circular economy perspective. It destroys material value and contributes to emissions. It should be considered only for non-recyclable waste, not as a default end-of-life plan.

Design Implications and Strategic Choices

Understanding the sorting and recycling processes leads directly to smarter design strategies. For example:

Selecting PET (#1) or HDPE (#2)—which are highly recyclable and accepted in most recycling streams where the product is used—can enhance the likelihood of successful material recovery.

Avoiding problematic resins like PVC (#3) or polystyrene (#6)—which are often rejected or contaminate other streams—can prevent the product from becoming landfill-bound.

Designing with monomaterials, clearly labeled resins, and minimal surface treatments improves both sortability and recyclability.

Choosing adhesives, labels, and colorants that don’t interfere with detection or processing makes recycling more efficient and less costly.

In short, designing with recyclability in mind means aligning product specifications with the limitations and strengths of existing recycling systems. Engineers must think holistically—not just about what the product is, but what it becomes after use. In doing so, they move beyond “can this be recycled?” to a more pragmatic question: “Will this actually be recycled?”

This shift in mindset—paired with technical understanding—allows for responsible, sustainable material choices that serve both the product and the planet.

2. Design for Monomaterial Construction

Products comprising a single type of plastic—monomaterial construction—are inherently easier to recycle. By eliminating the need to separate dissimilar materials, monomaterial products reduce the burden on sorting systems and improve the purity and marketability of recovered recyclate. A notable example is the transition of toothpaste tubes from laminated, multi-layer structures to monomaterial HDPE, making them compatible with standard HDPE recycling streams.

However, pursuing monomaterial design often requires reconsidering deeply embedded engineering conventions. Components that are traditionally made from metal—such as springs, fasteners, pins, or reinforcements—must be redesigned using plastics or eliminated altogether. For instance:

Metal screws might be replaced with plastic snap-fit joints, which require tighter dimensional control and tolerance management.

Metal springs could be substituted with integrated plastic flexures, which must be carefully engineered for fatigue resistance and consistent load response.

While these substitutions enable single-material recovery, they introduce new assembly, durability, and tolerance challenges that must be addressed through robust mechanical design and material testing.

Engineers should aim to:

Minimize the number of distinct material types used in the assembly.

Integrate mechanical functionality directly into plastic forms when possible.

Leverage finite element analysis (FEA) and fatigue modeling to validate plastic alternatives to metal components.

This shift often requires a more nuanced design process, but it aligns directly with the principles of the circular economy. Simplified material streams reduce manufacturing costs, eliminate disassembly steps, and improve recyclability—making monomaterial construction a cornerstone of sustainable product design.

3. Avoid Additives and Contaminants That Inhibit Recycling

Additives such as flame retardants, pigments, adhesives, and surface coatings can significantly compromise a plastic product’s recyclability. For instance, carbon-black pigments—commonly used to color plastic black—absorb near-infrared light and make it nearly impossible for automated sorting machines to detect the resin type. Similarly, adhesives that can’t be separated during the recycling process may degrade the quality of recycled plastic or clog equipment.

To improve recyclability, engineers can adopt several targeted strategies:

Use detectable pigments or avoid coloring altogether where possible

For example, many black plastic food trays or cosmetic containers are currently unrecyclable due to NIR invisibility. Switching to light-colored or NIR-detectable black pigments would allow these items to be properly sorted and recycled in standard facilities.Select adhesives and coatings that are water-soluble or thermally removable

Plastic beverage labels and shrink sleeves often use strong adhesives that remain on the bottle during washing and contaminate the plastic flake. Using wash-off labels or laser-marked branding can dramatically improve recyclability while preserving brand identity.Design for easy disassembly so contaminating components (e.g., labels, metal fasteners) can be removed

Consider the case of multi-part packaging, such as a squeeze bottle with a metal spring or complex cap assembly. Replacing metal springs with plastic flexures and ensuring the cap is made from the same material as the bottle simplifies recycling and avoids dissimilar material contamination.Avoid multi-layer films unless necessary

Many snack wrappers and frozen food bags use layered plastic films (e.g., PET/aluminum/LDPE) for performance. These are almost never recycled. Redesigning with a mono-material high-barrier film (e.g., all-PE or all-PP) can provide similar protection while being compatible with existing recycling streams.

These examples highlight how relatively small adjustments—such as changing pigment, adhesive type, or component structure—can significantly influence the recyclability of high-volume consumer goods. Engineers should evaluate these variables during material selection and assembly design, aiming to preserve functionality without compromising end-of-life recoverability.

Lifecycle Thinking: System Integration and Trade-Offs

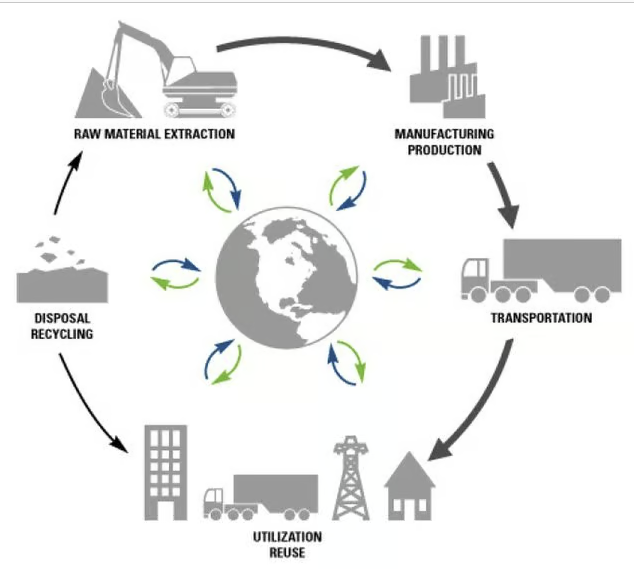

An engineer's role in designing for recyclability does not exist in isolation. Lifecycle assessment (LCA) tools can model the environmental impacts of different design choices, providing quantitative insights into:

Energy savings from material recovery.

Emissions reductions compared to virgin plastic production.

Trade-offs between durability and recyclability.

Beyond technical design, changing a company’s culture to prioritize sustainability and partnering with manufacturers who share this commitment can amplify benefits. For example, a shift towards monomaterial design often simplifies production and assembly processes, which can reduce manufacturing costs by minimizing the variety of raw materials and enabling streamlined supply chains. Manufacturers with environmental certifications or circular economy practices may also offer preferential pricing or improved logistics aligned with sustainable goals.

However, engineers and companies must also consider consumer recycling behaviors and habits, which can vary widely by region and demographic. A product that is perfectly recyclable in theory may fail in practice if consumers lack convenient access to appropriate recycling facilities or if educational outreach about proper disposal is insufficient.

To address this, companies should:

Promote reuse models as alternatives to immediate recycling, which can dramatically increase the environmental benefits by extending product life and reducing waste generation.

Design products and packaging with modularity or refillability in mind to enable multiple life cycles.

Leverage consumer engagement programs that educate and incentivize proper reuse and recycling practices.

This combined approach—designing recyclable products, cultivating sustainable manufacturing, and encouraging user reuse—opens new avenues for innovation and additional SKUs, such as refill packs or modular upgrade components, thereby strengthening a company’s market differentiation and environmental impact.

Successful integration of lifecycle thinking involves:

Cross-disciplinary collaboration between design, manufacturing, marketing, and sustainability teams.

Design thinking methodologies emphasizing empathy with end-users and real-world constraints.

Rapid prototyping and iterative testing to balance mechanical performance with circularity goals.

Systems-level evaluation ensuring changes do not inadvertently increase environmental burdens elsewhere.

Conclusion

The complexity of plastic materials and recycling systems demands that engineers expand their scope of design criteria beyond traditional metrics. By understanding resin properties and recycling technologies, prioritizing monomaterial construction, avoiding problematic additives, and incorporating lifecycle and systems thinking—including consumer behavior and company culture—engineers can drive meaningful improvements in product recyclability.

To translate these insights into practice, mechanical engineers should ask themselves actionable questions during the design process, such as:

Which resin type best balances product performance with compatibility in the most common recycling streams where my product will be used?

Can I redesign components traditionally made of metal (e.g., springs, fasteners) into plastic equivalents to achieve a monomaterial product without compromising durability or functionality?

Are the pigments, adhesives, and surface treatments I specify detectable and removable by standard recycling processes?

How can I simplify assembly to facilitate disassembly or reduce contamination during recycling?

What local recycling infrastructure and consumer behaviors will affect the actual end-of-life fate of my product?

Can my product be designed or marketed to encourage reuse, potentially creating new service models or SKU opportunities?

Is my company culture and supply chain aligned with sustainable design goals, and how can I collaborate across teams to embed sustainability throughout the product lifecycle?

By systematically reflecting on these questions and integrating the answers into design choices, engineers can not only reduce environmental impacts but also create more cost-effective, innovative, and future-proof products. Sustainable design is no longer optional—it is essential for engineers committed to advancing both technology and stewardship of the planet.

Make sure to follow the link to keep up with us! You can get a heads up with events we’ll be at, content we have coming up, and much more!