Selecting the Right Silicone

Key Considerations for Medical Device Innovation

In the dynamic and highly regulated world of medical‑device development, the right material choice can mean the difference between success and costly redesigns — especially when it comes to silicone. While many assume “silicone” is a single material, in reality there are numerous grades, chemistries, and processing routes, each suited to different applications in the medical realm.

Most people don’t fully understand the variety of silicone types, their specific applications, or the manufacturing processes involved. It's often mistakenly assumed that working with silicone is just like plastic injection molding — but this is far from the truth. Silicone requires different curing systems, mold designs, and handling considerations, especially when working with low-pressure molding or biocompatible grades.

This article looks at the major factors you should evaluate when choosing silicone for a medical‑device application — from material type to processing method, from regulatory/sterilization compatibility to manufacturing partnerships — and provides a consolidated view of how to make the right choice.

1. What is Silicone Rubber (and why does it matter?)

Silicone rubber is an elastomeric (i.e., rubber‑like) material whose backbone is largely composed of silicon‑oxygen (Si–O) bonds — a structure that gives it distinct advantages. According to LEADRP:

Silicone rubber is one of the most versatile elastomeric materials, used across industries from consumer goods to medical devices.

Typical manufacturing steps include mixing of base polymer + fillers/additives, compounding, shaping (extrusion, molding), vulcanization (cross‑linking) and post‑treatment.

It’s characterized by high flexibility, wide temperature tolerance, chemical stability and biocompatibility when medical grades are used.

For medical devices, these characteristics translate to: stable performance under heat or cold, durability under repeated use, minimal risk of degradation, and the ability to form complex shapes (e.g., tubing, over‑molds, patient‑contact surfaces).

2. Material Variants & Properties (Durometer, Chemistry, etc.)

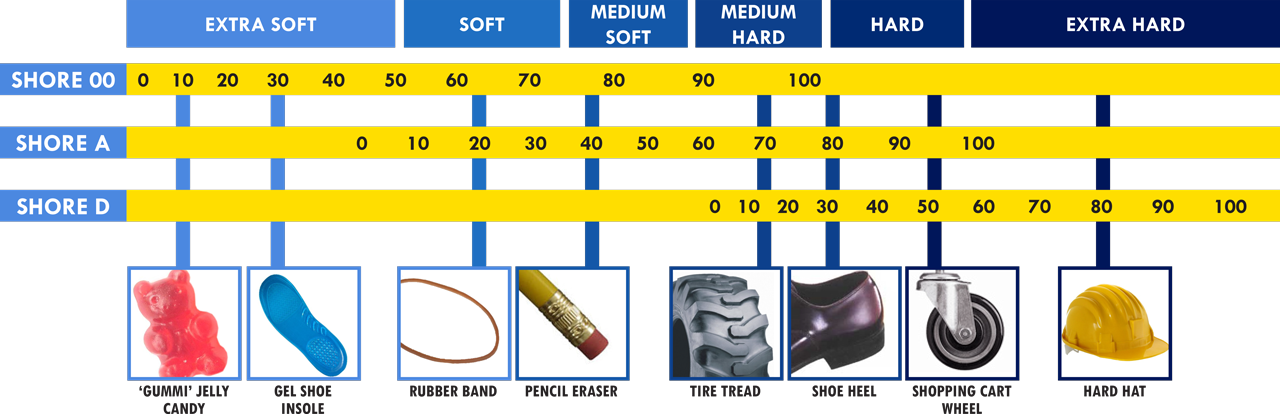

Hardness / Durometer (Shore Scale):

One of the first decisions is how soft or firm the silicone needs to be — often specified in Shore A or Shore 00 scales. A softer silicone may be used for patient‑interface components (pads, wearable devices) while a firmer one is better for structural or over‑molded parts that need rigidity.

Chemistry & Cure Type:

Silicone rubber can be cured via different mechanisms: room‑temperature vulcanisation (RTV), high‑temperature vulcanisation (HTV), addition vs condensation cure systems.

Some silicones are liquid silicone rubber (LSR) – two‑part, low viscosity, suited for injection molding. Others are high‑consistency (HCR) solid rubbers better for extrusion/compression molding.

3. Application & End‑User Experience Considerations

Every medical device has unique functional demands — the silicone part could be a tubing, patient contact pad, over‑molded grip, encapsulation, or wire over‑mold. Thoughtful specification is essential.

Many people don’t think outside the typical use cases when incorporating silicone, or they underestimate how its properties will impact the end-user experience. Whether it’s how a patient interacts with a wearable, how a clinician grips an instrument, or how a component holds up under sterilization and repeated use, these decisions directly affect usability, safety, and product perception. Overlooking these factors early in the design phase can lead to discomfort, premature failure, or a product that simply doesn’t perform as expected in real-world clinical environments.

Patient Contact: For components touching skin or implanted, you’ll need medical‑grade silicone, very careful biocompatibility review, and for many devices, ability to sterilize without degradation.

Over‑molding / Wire Encapsulation: If you’re molding silicone around wires or other substrates, compatibility and the right molding process become critical (e.g., substrate surface prep, adhesion, shrinkage, thermal cycling).

Sterilization & Long‑Term Use: Many silicones can withstand autoclave or steam cycles, but adhesives, substrates or components assembled with them may fail. The bond between adhesive (e.g., cyanoacrylate) and silicone must be validated.

User Experience: A grip, a seal, a cushion — the tactile feel (softness, flexibility), durability (repeat use, repeated sterilization) and aesthetics (color, finish) all matter. The durometer selected, as well as processing quality, influence all of these.

4. Processing & Manufacturing Strategy

We’ve covered the subject of adhesion with silicone previously — and how it can be a rather tricky thing to get right. It's often overlooked during stress testing, especially because it's difficult to visually assess bonding between two silicone or dissimilar surfaces. Failures can go unnoticed until the product is already in the field. With that said, I’m leaving this callout here as a reminder, but highly recommend reviewing our more in-depth article on silicone adhesion for a deeper dive.

What I really want to focus on in this section is the manufacturing process, because it is wildly misunderstood.

Many people assume silicone processing is just a version of plastic injection molding — but it’s not. The behavior of silicone during molding, curing, and demolding requires its own set of tools, techniques, and expertise. Without this understanding, teams often run into failures, poor part quality, or extended timelines.

Molding Method:

When it comes to molding silicone, the process differs significantly from standard high-pressure injection molding used for thermoplastics. Silicone is typically processed using low-pressure injection molding (LPIM) or compression/transfer molding, which better accommodate its unique flow and curing behavior.

In LPIM, a low-viscosity, two-part silicone is injected into a pre-heated mold, where it cures before being demolded. Unlike thermoplastics, which require rapid cooling to solidify, silicone needs heat to initiate crosslinking and cure the material. This reversal in thermal strategy — heating instead of cooling — offers significant flexibility during prototyping.

Because of this, many teams are able to use 3D-printed molds (typically via FDM or SLS) to test concepts and iterate on designs quickly. These molds are particularly valuable in early development when multiple durometers, geometries, or material properties are being evaluated.

However, when scaling to production, printed molds usually give way to properly machined metal molds that provide the consistency, durability, and thermal performance needed for higher volumes and regulatory compliance.

Finally, it’s critical to partner with a manufacturer who specializes in silicone processing. Experience with thermoplastics alone is often not enough — the behavior, tooling, and nuances of silicone require specific knowledge to ensure success from prototyping through full-scale production.

Choosing the wrong partner can lead to missed or improperly executed manufacturing steps, misunderstood material behavior, or a prototyping phase that drifts far from the final production quality. This not only wastes time and money but can also result in flawed assumptions about part performance, adhesion, or durability — all of which are much harder to correct late in the development cycle.

Tooling / Mold Design Considerations:

Designing molds for silicone requires a different mindset than designing for traditional thermoplastics — largely due to silicone’s unique thermal conductivity and curing behavior. Since silicone cures with heat rather than cooling, the mold material, venting, and heating system all need to be carefully considered. Poor thermal design can lead to inconsistent curing, bubbles, or incomplete fills.

Silicone tends to cure more slowly than plastics and exhibits different shrinkage and flow characteristics. As a result, mold design must reflect these behaviors, accounting for proper flow paths, venting, and temperature control throughout the part geometry. Even though silicone's flexibility allows for molding with little to no draft angle, that doesn’t mean you should skip it altogether. Including appropriate draft still helps with clean demolding, longer tool life, and less mechanical stress on the part — especially in production settings.

During prototyping, 3D-printed molds (using FDM or SLS) can be a cost-effective and rapid way to iterate. However, for production, it's best to move to metal molds with refined venting and thermal properties that can withstand repeated use and deliver consistent cycle times.

Also worth noting: because of silicone’s high fluidity, it's often unnecessary — and even counterproductive — to maximize injection pressure. Instead, you can allow the silicone to flow and settle naturally into the mold using a slower, more controlled fill cycle. This reduces the risk of trapped air, voids, or internal stresses, and results in a cleaner, more uniform cure.

Silicone rubber is a powerful material for medical-device innovation — thanks to its flexibility, biocompatibility, and durability. But as we’ve seen, choosing the right silicone means much more than simply selecting “silicone.” It requires specifying the correct grade, understanding how it will be processed, ensuring compatibility with substrates and adhesives, designing for sterilization, and partnering with the right manufacturer.

By combining a solid grasp of silicone fundamentals (as outlined in the LEADRP article) with application-specific demands — like tactile feel, over-molding, regulatory compliance, and long-term performance — you set the stage for a smoother design-to-manufacture path. In the competitive and highly regulated medical-device space, that early investment in material and process specification pays off in reliability, development speed, and fewer late-stage surprises.

We also strongly advocate for the use of silicone — when appropriate — because of its versatility and the speed at which it can be integrated into prototypes. With relatively low tooling investment and wide processing flexibility, silicone offers a fast, cost-effective way to add functionality, usability enhancements, or patient-facing features early in development — helping teams learn faster and iterate more effectively.